Edward Thorp Casino

- Edward Thorp Beat The Dealer

- Edward Thorp Northwestern

- Edward Thorp Casino Atlantic City

- Edward Thorp Notes Uci

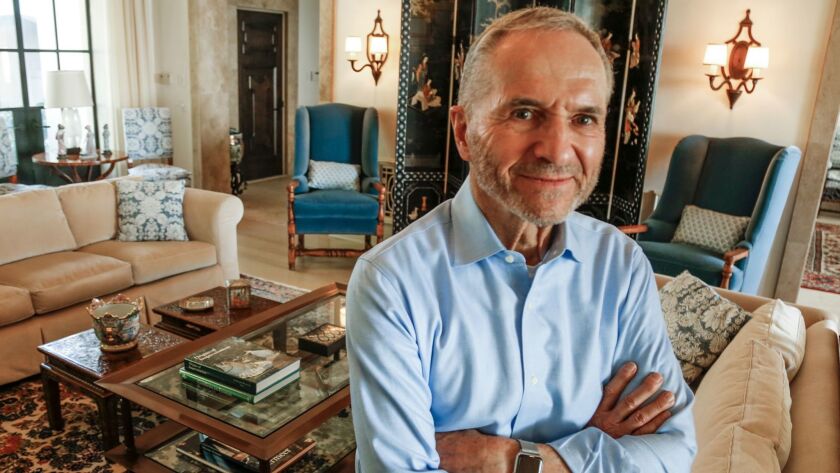

There’s a strong chance that the average person on the street has never heard

of Edward O. Thorp. For those who engage in blackjack or hedge fund management

on a regular basis, however, his name may loom as large as anyone else in those

fields of endeavor.

Edward O Thorp, the 84-year-old inventor of card-counting, was once the target of a suspected Mob hit. The revelation comes in Thorp’s new autobiography, A Man for All Markets, published this week. Jan 24, 2017 About Edward O. Thorp Edward O Thorp is widely known as the author of the 1962 Beat the Dealer, which was the first book to prove mathematically that blackjack could be beaten by card counting, and the 1967 Beat the Market, which showed how warrant option markets could be priced and beaten. With that in mind, Edward O. Thorp is a name that will always be remembered by blackjack fans. He had an undeniable passion for the game and if you want to experience the excitement of blackjack then visit Lucky Nugget Casino. Next time you find yourself at a blackjack table, adding and subtracting ones as you count your way through a shoe of cards, and, hopefully make a bit of money in the process, take a moment between hands to thank Edward O. He is the university math professor turned stock-market genius who invented card counting, wrote a bestselling book called “Beat The Dealer” and can be considered. Many gambling legends make their mark in casino gaming and fade away. While these legends may get rich from their exploits, they never attain fame in any other niche. Edward Thorp is an exception to the norm. The “Father of Modern Card Counting” is not only a blackjack icon but also an investment guru.

Edward Thorp Beat The Dealer

If you fall into the former category, it’s our hope that this Edward Thorp

biography can familiarize you with one of the titans of statistical gambling.

For those who already have a basic knowledge of the man, our detailed biography

of his life is sure to present some facts that have previously slipped between

the cracks. In either case, you should come away from this article with a

newfound appreciation for a true pioneer.

Early Years

Edward Oakley “Ed” Thorp was born in Chicago, Illinois on August 14th, 1932.

His father was a veteran of World War I, and the senior Thorp had met his future

bride after returning home from combat.

Thorp’s father was a strong proponent of education, and he worked hard to

make sure his son would have a solid foundation of knowledge to draw upon

throughout his life. The benefits of the elder Thorp’s efforts were evident

early on, as Edward could mentally calculate the number of seconds in a year by

the age of seven.

When America entered World War II, Thorp’s father was once again called upon

to serve his country. The absence of the family breadwinner created difficulties

when it came to paying the bills, so Edward’s mother took a job at Douglas

Aircraft to make ends meet.

With his father gone and his mother working, the only child of the Thorp

family was left with lots of free time. Instead of getting in trouble, however,

he pursued a diverse number of hobbies ranging from making explosives (and

detonating them) to playing chess with opponents via a HAM radio.

His father managed to survive yet another world war, and the elder Thorp

relocated his family to Lomita, California when Edward was 10. Ed’s desire for

knowledge and overall intellect continued to flourish, despite being enrolled in

a school that was rated as one of the worst in the area.

Higher Education and Teaching

After graduating from high school, Thorp used his overall intellect and keen

talent for math to gain acceptance to UCLA. He received his bachelor’s degree in

physics in 1953, and this was followed by a master’s degree in 1955.

He then set his sights on a doctoral degree in mathematics, and during this

period he became interested in the math associated with gambling (specifically

roulette). He decided to dispute the long-held notion that games of chance

couldn’t be beat.

Thorp received his PhD in mathematics in 1958, and he began working as a

professor at MIT the following year. He held this position until 1961, when he

transferred to New Mexico State University and taught mathematics until 1965.

At this stage, Thorp began his long affiliation with the University of

California, Irvine. He taught mathematics at the college from 1965 to 1977, and

then became a professor of both mathematics and quantitative finance from 1977

to 1982.

Edward Thorp Northwestern

A Wearable Computer

While teaching at MIT, Thorp continued his fascination with using mathematics

to crack the secrets of gambling. He spent hours observing the various games,

and he noted one element that stood out above all others. In a game such as

roulette, each spin was independent of one another, which meant that the odds

were the same regardless of when or where it was played. Blackjack, however, had

odds that varied, as cards being dealt from a deck altered the probability for

future hands (at least until the deck was reshuffled).

Around this time, Thorp read an article about blackjack strategy in a

statistical journal. This further fanned the flames of interest, and he decided

to take his wife on a trip to Las Vegas. While the couple enjoyed modest success

at the blackjack table, Thorp left convinced that a perfect system of play

existed. All it required was someone to come along and discover it.

To help in his initial efforts, Thorp used two main tools. The first was an

IBM 704 computer, which Thorp was able to operate after teaching himself the

computer language known as FORTRAN. The second was the Kelly criterion, a

formula developed in 1956 by J.L. Kelly, Jr. to determine the ideal size of a

series of wagers.

As his research intensified, he brought fellow mathematician Claude Shannon

on board. Claude and his wife would accompany the Thorps on trips to Vegas, and

this led the two men to create the first pocket-sized computer for the purpose

of advantage play (which is now illegal under modern-day casino rules).

At the time, a deck of cards wasn’t reshuffled after every hand, so it was

much easier to keep track of which cards had been played and which remained.

This was a major factor in helping Thorp create his system, and casinos later

adopted a policy of shuffling after every hand in order to combat would-be card

counters.

Following careful research and analysis, Thorp created several strategies

that he felt provided the player with a stronger chance of winning. His favorite

was known as the 10 Count System, and it’s explained in the following section.

The 10 Count System Explained

First presented in Edward Thorp’s book, Beat the Dealer, the 10 Count System

is a method that allows players to increase their odds of winning while playing

blackjack. It’s by no means the earliest example of a card counting system, but

it’s notable for being the first made widely available to the general public.

The importance of this fact can’t be overstated, as it opened up gambling and

the game of blackjack to a whole new pool of players.

The system is meant to be used with a single deck of cards, and the goal is

to reduce the house edge by placing larger wagers when the player has a greater

chance of achieving a valuable hand. Counting begins when a fresh deck of cards

is dealt, and the player is tasked with assigning a numerical value to each

face-up card on the table.

If a card is worth 10 points in blackjack, then Thorp’s system assigns it a

value of negative nine. All other cards, meanwhile, are given a value a four. As

the player keeps a running count of the cards, they can get an idea of when they

have the best chance to receive a 10-point card. For example, a count of zero

indicates that there are 2 1/2 4-point cards for every 10-point card in the deck.

While this system is effective for single-deck games of blackjack, there’s

simply too much variation when it comes to larger decks. Las Vegas initially

tried to counter the 10 Count System by introducing new rules, but players

rebelled and refused to play these games.

Instead, the casinos eventually started introducing games with multiple decks

dealt from a shoe, and they were able to convince players to accept these

changes over time. This has rendered Thorp’s system largely ineffective for most

modern forms of 21, although it would become the basis for more advanced methods

of play over the decades.

Edward Thorp Casino Atlantic City

Taking on the Casinos

Armed with a winning strategy, Thorp was ready to put his research to the

test by making a serious run at the casino blackjack tables. He understood

bankroll management quite well, however, and he therefore realized he would need

someone to bankroll him.

He found his financial backer in Manny Kimmel, a respected gambler with lots

of money and possible connections to the mafia. Another individual may have also

been present, but the exact details tend to vary from one source to the next.

Kimmel wasn’t named directly in Beat the Dealer, instead being given the moniker

of “Mr. X.”

The first stops on their trek were Reno and Lake Tahoe, and Thorp had been

given a $10,000 investment to play with, courtesy of his newfound partner(s).

One of the main destinations was a now-defunct Reno casino known as Harold’s

Club, and Thorp managed to win $500 within 15 minutes using his system. While

the system didn’t always work, he wound up with an $11,000 profit by the end of

the weekend. After that, he never had to ask Kimmel for another penny.

Thorp eventually moved on to Las Vegas, but his ability to rack up

significant wins drew the attention of eagle-eyed security agents. This got him

ejected from a number of Vegas casinos, and Thorp had to resort to a number of

disguises to keep gaining admittance. In fact, he soon adopted the practice of

carrying a notebook on his trips, allowing him to keep track of his various

affectations and disguises. In addition to blackjack, he put together a baccarat

team that enjoyed a respectable amount of success during this period.

Beat the Dealer: A Winning Strategy for the Game of Twenty-One

Word of Thorp’s system and exploits soon spread throughout the close-knit

community of serious gamblers, and the mild-mannered professor was inundated

with requests for his secrets. Thorp had always enjoyed the intellectual

challenge more than the financial benefits, so he decided to put his thoughts

and theories into book form and make it available to anyone who was interested.

The first edition of Beat the Dealer was published by Vintage Books in 1962.

The tome clocked in at over 200 pages, and it was packed with everything from

card counting systems to tips on how to recognize cheating.

Instead of undergoing the usual peer review process for an academic work,

Thorp simply released it onto the market. Some wondered if the mob might respond

by sending a hitman to assassinate Thorp, but nobody resembling Joe Pesci ever

materialized. Beat the Dealer went on to sell more than 700,000 copies and make

the New York Time Bestseller List, a remarkable feat considering that gambling

was such a niche category in the 1960s.

Despite the success of the book, however, a number of critics argued that the

strategies presented were difficult to apply in real-world situations. Ever the

serious academic, Thorp took these criticisms to heart and set out to further

refine his ideas. Luckily, he would get some serious help in the form of fellow

egghead Julian Braun.

Julian Braun and Hi-Lo Card Counting

The publication of Beat the Dealer drew attention from a lot of individuals,

but one of the most notable was IBM computer programmer Julian Braun. The

mathematician and former Marine wrote to Thorp and requested a copy of his

blackjack computer program, which Edward was happy to provide.

Braun used an IBM 7044 mainframe computer to further refine the strategies

laid out by Thorp, running 9 billion blackjack simulations in the process. Over

the next four years, Braun perfected the Hi-Lo Blackjack System, which was more

accurate that Thorp’s original 10 Count System.

When Beat the Dealer was offered in a revised form in 1966, Braun’s Hi Lo

System was included with the following quote from Thorp,

“Braun’s detailed

blackjack calculations, based on his extensions and refinements of my original

computer program, are the most accurate in existence, and he has kindly allowed

them to be used throughout this revised edition.”

Like all forms of card counting, Hi-Lo requires the player to assign a

specific value to each visible card. In this case, the values are as follows:

- 2 through 6 = +1

- 7 through 9 = 0

- 10 through Ace = -1

This is known as a “balanced system,” as the count of all cards in the deck

equals zero. High cards are more beneficial to the player, so their value is set

at -1. Low cards, meanwhile, benefit the dealer, so their value is set at +1.

When the count is high, this means more high cards should exist in the hand, and

therefore the player should place larger wagers.

To properly use the system, you must keep up with the running count and the

true count. The former is just what it sounds like: a running total of the value

of all cards played during a hand. The true count, meanwhile, allows the player

to determine if they truly have an edge over the dealer.

In a single deck version of the game, the true count is determined by

dividing the running count by the number of cards yet to be played.

Unfortunately, it’s almost unheard of to find a single-deck game of blackjack

these days, so the player is now required to estimate the number of decks still

in the shoe and divide this by the running count.

Additional Literary Works

While most gamblers and members of the general public remember Thorp for Beat

the Dealer, he wasn’t content to rest on his laurels as an author. He has penned

a number of other works, and all of these are still in print.

- A Man for All Markets: From Las Vegas to Wall Street, How I Beat

the Dealer and the Market (2017) - A Winning Bet in Nevada Baccarat (2013)

- The Mathematics of Gambling (1984)

- Beat the Market: A Scientific Stock Market System (1967)

- Elementary Probability (1966)

A comprehensive look at Thorp’s life,

from his time as a card counter to his career as an investor.

A re-publication of a

1963 research journal article entitled “A Favorable Side Bet in Nevada

Baccarat.”

An analysis of gambling games

such as blackjack, baccarat, and backgammon, as well as tips on proper money

management. Most of the items in this book are reprinted columns that Thorp

wrote for Gambling Times magazine.

Thorp

takes his skills at mathematics and analysis and applies it to the world of

investing.

A scientific text on mathematics

and probability.

In addition to the books listed above, Thorp has written a wide range of

academic papers on game theory, functional analysis, and probability.

Investment Wunderkind

After Beat the Dealer became a sensation, Thorp found it increasingly hard to

enter a casino without being spotted and ejected by security. He therefore

decided to take a break from the world of gambling, turning his attention

instead to investing.

Working alongside Sheen Kassouf, Thorp used his knowledge of statistics and

analysis to find and locate pricing anomalies in the securities market. This led

to the invention of delta hedging, as well as the creation of what’s now known

as the Black-Scholes formula.

In 1967, Thorp published his findings and advice in a book titled Beat the

Market. While it didn’t sell as well as Beat the Dealer, it had a major

long-term impact on the world of investing. Two years later, Thorp and partner

Jay Regan would launch the first market-neutral derivatives based hedge fund

(known as Princeton/Newport Partners).

While still teaching, Thorp founded Edward O. Thorp & Associates, which he

continues to run as of this writing. His first hedge fund returned 15.1% over 19

years, while his overall personal investments have yielded an average return of

20% for 28.5 years (as of 1998).

Induction into the Blackjack Hall of Fame

Edward Thorp Notes Uci

In 2002, it was decided that the Blackjack Hall of Fame would be created to

honor the contributions of various men and women to the game of 21. The initial

ballot was appropriately comprised of 21 players, experts, and authors, and

voting was held in order to cull down the list. Casino owners and the general

public were invited to participate, although those who derived their primary

income from blackjack had the greatest influence on the voting process.

The first class of the Blackjack Hall of Fame was announced at the 2003

Blackjack Ball, which is always held in a secret location to elude minions of

the casinos. A total of seven individuals were inducted, and Thorp was among

those honored. The complete list included the following:

- Edward O. Thorp

- Ken Uston

- Al Francesco

- Stanford Wong

- Tommy Hyland

- Arnold Snyder

- Peter Griffin

Philanthropy

In 2003, Edward O. Thorp and his wife, Vivian, donated $1 million to the

University of California, Irvine, to attract promising mathematicians to the

college. According to Thorp,

“Vivian and I have greatly benefited from the

knowledge I have acquired in mathematics and my association with the

mathematical community. It’s our chance to give back, in a modest way, to

mathematics, mathematicians, and a great university.”

Conclusion

As you might have guessed, Edward Thorp has used his mathematical genius to

make himself a multi-millionaire. While his blackjack endeavors brought him a

certain level of fame and a sizable return on Beat the Dealer, it was his

transition to the world of investing that moved him up several tax brackets.

Now in his golden years, Thorp enjoys semi-retirement with his wife and

family. His legacy in the world of gaming is assured, and he also enjoys the

respect of his peers throughout the mathematics community. Not bad for a kid who

used to pass the time by blowing things up.

Four years before the 1962 publication of Thorp’s book, he was contemplating ways of beating roulette and had already created the world’s first basic-strategy card – those pocket-sized laminated rectangles that tell players each correct play to make in blackjack. As related in his new book, “A Man For All Markets,” in 1958 Thorp and his wife decided to spend their Christmas holiday in Las Vegas, playing a bit of blackjack.

At the time, blackjack was a pursuit in which players had no shot at winning money over the long run. In fact, they were likely to lose lots of cash as a result of random, shoot-from-the-hip play. Enmeshed in the world of games and math, though, Thorp had been made privy to an approach for playing blackjack – which later became known as “basic strategy” – that had been devised by four men in the US armed forces. It reduced the house edge to .62-percent.

Thorp sat down with a bankroll of $10 and his homemade card that told him what to do with all possible hands against every dealer up-card. He had $8.50 left before quitting – and becoming optimistic about conquering the game by learning in his own way how to play it. Dealers and fellow players laughed at him for consulting his card and making plays – hitting with a soft 18 against the dealer’s 9, for example – that seemed silly then but is the norm now. “The atmosphere of ignorance and superstition surrounding the blackjack table that night had convinced me that even good players didn’t understand the mathematics underlying the game,” he writes in his book. “I returned home intending to find a way to win”.

In the library of UCLA, where he toiled in the math department, Thorp worked numbers and reached the breakthrough conclusion that the game of blackjack changes based on cards remaining to be dealt. In 1959, Thorp snagged a professorship at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After learning to program on the school’s mainframe computer, he created a system for keeping track of cards that had already been dealt, betting higher when the remaining cards presented advantages for players, betting lower otherwise and deviating from basic strategy when the math deemed that such a move would be correct.

In short, he came up with the system that card counters still use today. By 1961, after Thorp went public with his findings, he teamed up with a pair of New York businessmen who were eager to back a test-run in Reno, NV. They put up a total of $10,000 (equal to 80,000 in 2016 dollars). In short order, Thorp was spreading from $50 to $500 in a single-deck game that was dealt to the bottom. Uncomfortable with his winning ways, casino owners demanded that their dealers shuffle as often as necessary to prevent the mathematician from consistently winning. Clearly, Thorp’s system worked.

After a few days, though, he experienced the bane of every card counter who’d go on to follow him. “The casino had barred us from play,” he writes. “I asked the floor manager what this was all about. He explained, in a friendly and courteous manner, that they had seen me playing the day before and were puzzled at my steady winning at a rate that was large for my bet sizes. He said that they decided that a system was involved.”

They were right. In the end, it yielded $11,000 of profit via just 30 hours of play (this would be today’s equivalent of an $88,000 profit, nearly $3,000 per hour). By the summer of 1961, Thorp was writing “Beat The Dealer,” a book that would introduce the world to his breakthrough strategy for playing blackjack with a mathematical edge that turned the tables on the casinos. The book became a bestseller. Legions of blackjack fanatics followed its concepts and earned fortunes.

But the casinos did not take well to losing and Thorp, who began teaching at University of New Mexico, took to wearing disguises in order to thwart eagle-eyed pit-bosses and security personnel. He and his book got written up in Sports Illustrated and Life magazine. Bookstore owners couldn’t keep it on their shelves. Freaked-out casino magnates held a secret meeting at the Desert Inn to try figuring out what to do about Thorp and those who had been inspired by him. Sin City’s local newspaper, The Las Vegas Sun, retaliated with a story attempting to debunk card counting.

Obviously, the reporter was wrong. In the wake of Thorp’s book, blackjack teams – like the famous MIT Team, immortalized in the movie “21” – formed and flourished. Advanced gambits, such as the Big Player strategy (in which someone slips onto the table, betting only when the count is positive), made profits soar and left maneuvers difficult to detect. As Thorp writes, “I found myself barred, cheated, betrayed by a representative of the gaming control board and generally persona non grata at the tables. I felt satisfaction and vindication when the great beast panicked. It felt good to know that, just by sitting in a room and using pure math, I could change the world around me'.

By 1964, as advantage play spiked, Thorp forsook blackjack for a bigger challenge: the casino known as Wall Street. Having recognized that “gambling is investing simplified,” he went on to beat that larger, more challenging game, reaping sums of money that capitalize on inefficiencies and make advantage-playing profits look like chump change. Clearly, as he has proven via successful runs against blackjack and the stock market, “Great investors are often good at both”.